Some patients with chronic pain need long-term support. Ian A McMillan meets two physios who don't look for a 'quick fix'

Memory and concentration problems, dashed hopes, an impaired sense of identity, loss of confidence, depression and panic attacks. These are some of the ingredients in an emotional cocktail affecting people living with long-term pain, according to Neil Clark, a highly specialist physiotherapist.

Mr Clark, who is based at Queen Margaret Hospital, Dunfermline, about 20 miles north of Edinburgh, has compiled a list of problems highlighted by patients with chronic pain who attend group sessions.

In the past, people with chronic pain tended to be branded as ‘heart sink patients’ by unsympathetic GPs, because they pitched up repeatedly at surgeries and failed to respond to a succession of interventions. But for Mr Clark, a band 7 physio with the Fife integrated pain management service, they are an endlessly fascinating and challenging group, meriting sophisticated, tailor-made support from a multidisciplinary team.

Mr Clark’s colleague, physio team lead Paul Cameron, says the goal is to promote perseverance or ‘stickability’. ‘Patients may face many setbacks along the way, and may become discouraged, ’he explains. ‘Research shows that a clinician’s attitudes can affect the quality of the consultation, the treatment given and even whether a patient is referred to a specialist service or gains access to appropriate medication. There could be fears about patients becoming addicted, from both the clinician’s and the patient’s perspective.

‘As physios we are often trying to figure out the patient’s belief system or how things in the past have impacted on them. Some are “in mourning” for a past life – which, in reality, might not have actually been as good as they now imagine.’

Contrary to a layperson’s expectations that people with chronic pain tend to be middle-aged or older, the patients seen at the Fife Integrated Pain Management Service have a wide spectrum of ages. Their conditions are also broad – including fibromyalgia, chronic back pain and complex regional pain syndrome. Some have pre-existing conditions, such as multiple sclerosis, or are recovering from having had a stroke or chemotherapy.

‘We appreciate that change can take time,’ says Mr Clark. ‘One of my colleagues said what we do is “slow rehabilitation” in that we take people’s social circumstances into account. By the time patients get referred here, they can be depressed and their motivation and self-esteem is very low.’

Battered self-esteem

For some, chronic pain can be the latest in a series of blows to an already battered self-esteem. ‘Some patients have backgrounds where they might have struggled with school and education and may not have had role models who made it in the world of work.

‘Some lack any experience of success in their lives and find it difficult to overcome chronic pain. Of course this is not true of all people from this background, nor is it the case for all people who develop chronic pain. But social context is hugely powerful in people with persistent pain and cannot be ignored.’

The service covers a population of 350,000. Much of the catchment area is relatively rural, but there are pockets of post-industrial deprivation – many traditional jobs in mining or harbour work, for example, have declined or disappeared entirely.

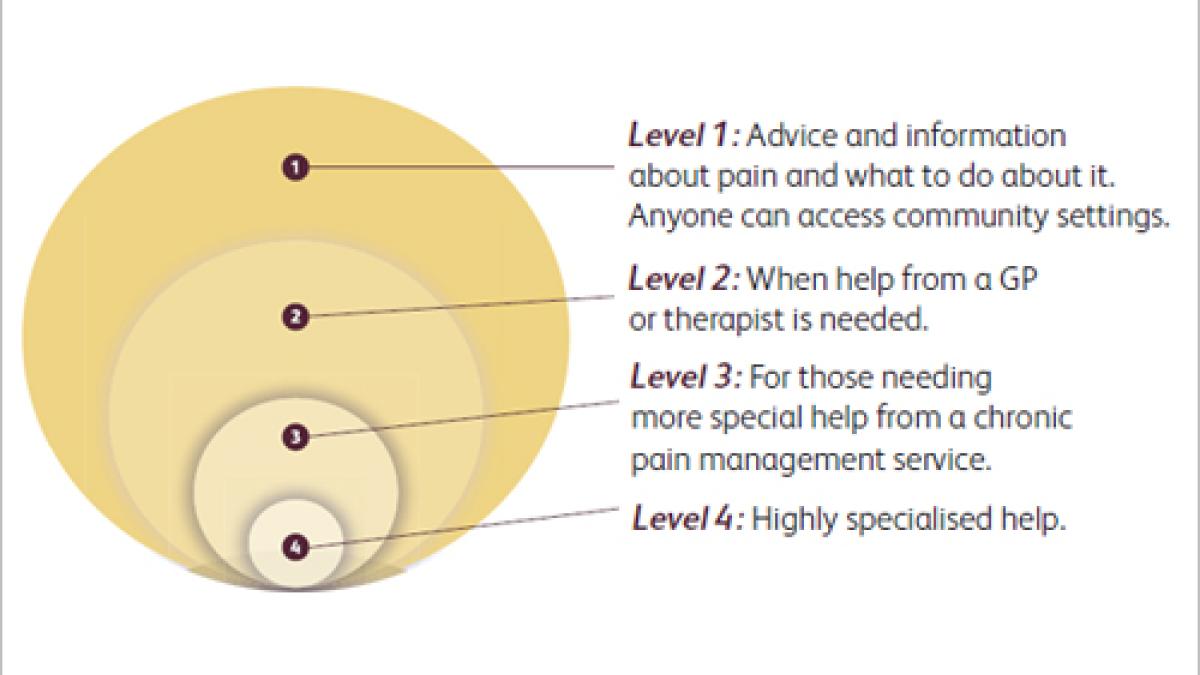

What makes the Fife pain service so pioneering – unique, even in Scotland – is that it is delivered in both primary care and secondary care settings. Indeed, it’s proved so influential that the Scottish service model for chronic pain is now based on it.

Unique service

Mr Cameron, who chairs the British Pain Society’s education committee and is the national chronic pain coordinator for the Scottish Government, explains its origins: ‘The plan to integrate the two arms of the pain service was put into effect in 2009. Physiotherapy had started contributing to the secondary care pain service in 1999 and the primary care pain service (known as Rivers) was set up in 2004.

‘What’s unique about us is that by having services based in primary care and secondary care we can cater for every patient’s needs. This means that if they can cope with an exercise and education-based pain management programme, they will be seen by the primary care, or Rivers, team.’

This consists of physiotherapy, pharmacy and physiotherapy technical instructors. ‘The secondary care team at Queen Margaret is for those requiring more individualised, multidisciplinary input. As well as physiotherapists, there are consultant anesthetists, a specialist nurse, an occupational therapist and clinical psychologists.’ There is a gym with equipment such as stationary bikes and running machines where patients often surprise themselves by beginning to exercise again.

Mr Cameron, a supplementary and now independent prescriber, can prescribe drugs ranging from paracetamol to morphine (the latter with a GP’s signed approval). ‘We try to give people medication at as low a level as possible, thus reducing the potential for harmful side effects, while still maintaining any benefits. As a physiotherapist with prescribing rights I can deal with a patient’s problems then and there, without waiting for them to be seen by a colleague.’

Staying on message

For Mr Clark, the ethos of the service is about helping patients to manage their own pain. ‘It’s a bit like teaching a child to ride a bike – they may initially need a lot of support and fall over a lot. But, with time and support, they can ride off into the distance and you can step into the background.’

A consistent approach is taken and patients receiving secondary care might see a range of professionals over time. ‘The important thing is that we all have the same ethos of supported pain self-management. No matter which professional they see, or the setting they are seen in, the message will be the same,’ says Mr Clark.

‘We are not generally looking at giving injections or medication in isolation: rather we emphasise, promote and demonstrate the skills of pain self-management to the patient. We might help them gain a better understanding of their condition, returning to an activity or to exercise. We use pacing strategies, relaxation, goal setting, reducing fear avoidance and so on.’

Mr Clark’s says his primary care colleagues often see patients in community venues, such as leisure centres. ‘This is important as it begins to de-medicalise the condition. Patients don’t have to go to a hospital or a health centre for their pain problems, and going to a leisure centre may actually be the best thing for them.’

New patients are triaged based on self-completed questionnaires and a decision is made on whether they are seen by the primary or secondary care service. The questionnaires give information on topics such as function, anxiety and depression.

Mr Cameron points out that pain cannot be measured or seen, and that people with chronic pain often have to grit their teeth and carry on with activities, such as going to work or taking their children to school. ‘Whereas most people can empathise with having a broken leg or toothache, they might wonder, given that the patient isn’t screaming or writhing in pain, just how much pain the person is enduring.’

Dundee research

Research conducted at Dundee University in one region of Scotland found rates of chronic pain that if extrapolated nationwide would mean 800,000 people are affected in Scotland, says Mr Cameron.

‘That figure is, I believe, a minimum, as not everyone will take part in a survey. Clearly 800,000 people are not being seen by chronic pain services and most people “manage” and just get on with things. This can have a knock-on effect on employment and some people find ways of dealing with it that are unhealthy – and they might be less likely to seek help from us as a result, unless the pain becomes very severe.’

For Mr Cameron, who is undertaking a PhD at Dundee University on a part-time basis, the ‘selling point’ of the Fife specialist service is that it sees patients who are at the ‘end of the road’.

‘Without us many of them would be described as “revolving door” patients, visiting their GP repeatedly and wouldn’t be able to contribute to society.’

Mr Clark adds: ‘We often work on educating the patients, helping them to understand that pain is not necessarily a sign of harm or damage, and that avoiding activities or exercise will make things worse in the long run. Through a combination of a better understanding and gently encouraging people to do things gradually, they become more active again and start to focus on what they can do rather than what they can’t.’

Self-reported effects of chronic pain

- others don’t understand/don’t see it

- sometimes feel will find some hope – disappointed

- sleep problems

- increased weight

- stiffen up

- weak muscles

- work issues

- panic attacks, anxiety

- benefits

- depression

- memory and concentration

- anger and frustration

- loss of identity

More information

Neil Clark is public relations officer for the Physiotherapy Pain Association professional network.

Physiotherapy works: chronic pain is available.

Author

Ian A McMillan

Number of subscribers: 2