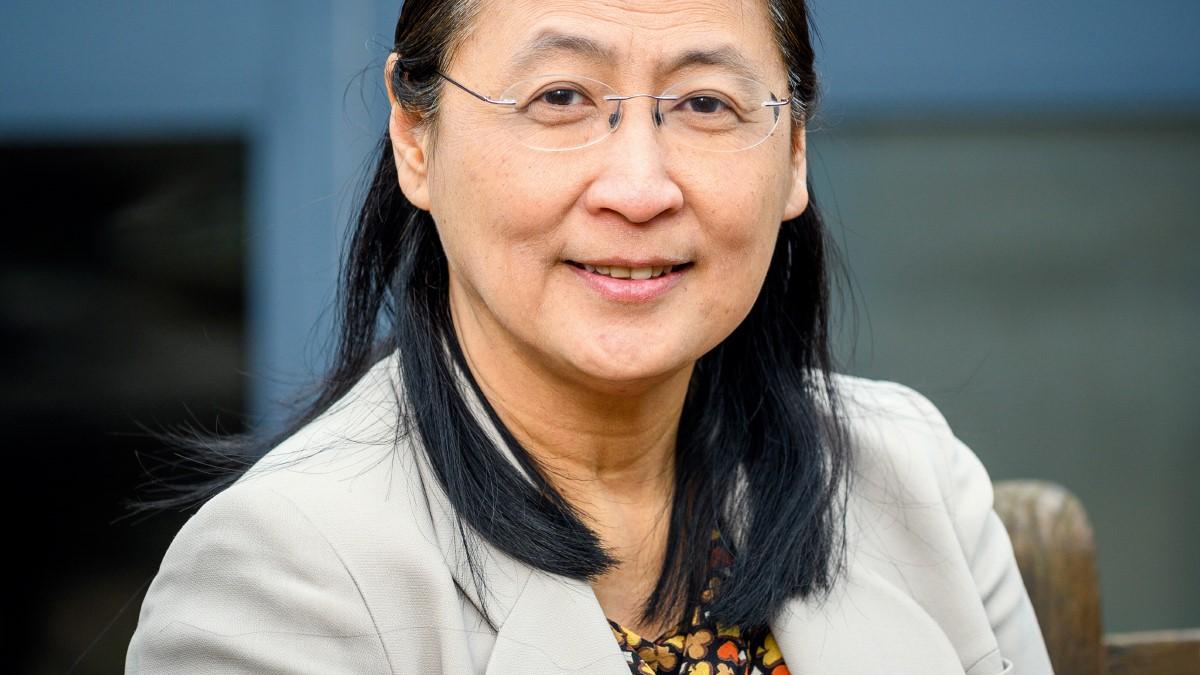

An interview with Professor Bee Wee, England’s national clinical director for end of life care

2020 started with a wonderful surprise for Professor Bee Wee when she was awarded a CBE in the New Year Honours List for services to palliative and end of life care. Yet when we meet on a rainy day in Oxford at Sobell House where Bee is clinical lead, there is no mention of her CBE. It’s not until after our chat that she emails to say she completely forgot to mention it!

Bee’s expertise in end of life care is certainly in demand. In addition to her role as consultant in palliative medicine and clinical lead at Sobell House, she is seconded to NHS England and NHS Improvement where she works three days a week as national clinical director for end of life care. She is also associate professor of palliative care at the University of Oxford. Her research interests include symptom management, rehabilitation, care of the caregivers and care at the very end of life.

Physios are core part of end of life care

Sobell House is located at Churchill Hospital in Headington, Oxford. It’s one of four hospitals under the umbrella of Oxford University Hospitals NHS Trust. Sobell House has an 18-bed inpatient unit, a community outreach team, a hospital palliative care team, day services and an education and research department. Physiotherapists are a vital part of the team, she says.

‘I’ve been very lucky in my career to work with some brilliant physiotherapists and occupational therapists both during my time in Southampton and now at Sobell House,’ Bee explains. ‘I see physios as being a core part of the end of life care team, we could not do what we do without them. They have a significant contribution to make when it comes to symptom management, pain management and also anxiety management. In both services where I’ve worked as a consultant, we’ve had physios that do a lot of home visits and are involved with day services too. In my view, physiotherapy makes an enormous difference to the quality of life of patients with life-limiting illnesses.’

First steps to specialising

Originally from Malaysia, Bee moved to Ireland when she was 15 to complete her school education and train as a general practitioner. She qualified in the late 80s. Her first role as part of junior doctor rotations was within Our Lady’s Hospice in Dublin. ‘I was actually the very first junior doctor to work within palliative medicine at that time as it was a new speciality in Ireland and the hospice had just appointed its first consultant,’ she says. ‘I loved it and after my three-month rotation came to an end, I continued to help out on weekends.’

She describes falling into the speciality almost by mistake. ‘I could happily have gone into either general practice or palliative care as both were of equal interest,’ she says. ‘But I was offered a medical adviser role in palliative care in Hong Kong and this drew me into the field. I was there for around two and a half years and enjoyed it but the system is very different there – I went from being a junior doctor to running the service.’

Physios increase confidence

Bee was eager to return to the UK when an opportunity to work as a palliative care consultant at Countess Mountbatten Hospice in Southampton arose. During her eight years in Southampton, Bee also became involved with the University of Southampton’s medical school. From her experiences in Southampton, she recalls a particularly memorable example of the important role physiotherapy has in end of life care.

‘It was fairly early on in my career as a consultant when I was talking to a physiotherapist colleague about a patient who was falling a lot at home,’ Bee explains. ‘I was eager to discuss ways we could help him to walk safer when she said what she could do is teach him how to fall safely. Once the patient had learned how to do that, he was much more confident about walking and this led to him falling a lot less. She also taught his wife how to help him get up after a fall in a way that was safe for both of them. I wouldn’t have thought about that, she came at it from a completely different angle. It made such a difference.’

At Sowell House, there is an eight-week patient education programme called Living Well that offers advice on symptom management including fatigue and breathlessness. Physiotherapists play a vital role within the programme. ‘Increasing people’s confidence is the big, big difference physios make,” she says. ‘In addition, they also increase the confidence of other professionals in a patient’s ability to mobilise and to function. They encourage others who might otherwise have been more cautious – they help to demystify it.’

Challenges to overcome

When asked if she feels improvements could be made around guidelines for end of life care, she considers this for a moment before answering. ‘The guidelines we have for palliative and end of life care have always included physiotherapy and occupational therapy contributions. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance has always recognised the role of physiotherapy within end of life care but maybe there is a need for guidance that is more physiotherapy-orientated. I wonder whether there is also a need for guidelines that physios working in palliative care could write for physios that don’t work in the field. It’s a good question.’

On the subject of challenges, the field itself can pose difficulties, she says. ‘A lot of colleagues who aren’t in this field find it hard to almost accept that people die. Trying to measure quality of life and improvements made is also harder because I suppose our most stable measure is people dying.

‘End of life care is also not very clear cut. A lot of my patients have long-term conditions but won’t need palliative care until they reach a certain point and that point is never very clear. My biggest challenge personally is constantly sitting in several worlds – consultant, strategic leadership and research – and not entirely belonging to any single one. A further challenge with end of life care is that funding has always been smaller.

In this country, there’s a greater reliance on charitable funding. In research also, the funding is much, much less for this field.’

However, Bee does feel there is better recognition of end of life care as part of undergraduate medical training. ‘When I think back to my older colleagues and their pioneering days, it was really very difficult then to get end of life care recognised. Whereas now, every medical student has this in their curriculum and most will also have end of life care in their final exam. All the different curriculums are better at recognising palliative and end of life care now.’

Making a difference

Bee has been seconded to her NHS England and NHS Improvement role for almost seven years now and feels she can make a difference by speaking on behalf of end of life care colleagues and patients to the wider NHS.

‘Part of my role is to set a direction so that we’re all heading the same way and we all have the same idea of what good end of life care looks like,’ she says. ‘Flying the flag for people with palliative and end of life care needs is a really important part of what I do. Because I’m clinically grounded, I’m also able to say when something that sounds like a good idea on paper just wouldn’t work in practice as sometimes the two can be very different.’

Despite the challenges working in end of life care poses, it offers numerous rewarding aspects. ‘You can make a difference to patients and their families in so many different ways,’ she says. ‘Some of it can be very, very small yet it’s something they will remember forever. There’s always a way of making a difference in this field and that is just endlessly rewarding.’

Number of subscribers: 1